Ibrahim Izzeldeen

In the winter of 2016 in Khartoum and at the request of my friend, the writer Abdul Latif Ali Al-Faki I undertook a search for his contributions which were published in the cultural dossiers of daily newspapers during the period of the Third Democracy at the National Records Office in Khartoum. Throughout my repeated visits to the archives, my attention was drawn to the bound volumes of the Sudan Governmental Gazette

–Al-Ghāzītah al-Sūdānīyah -the colonial newspaper which marked the first publication of its kind in Sudan. Whenever time permitted, I found myself delving into its pages, captivated by their historical texture, and began to digitally reproduce selected sections of their rich and varied content for closer study.

As I explored the Gazette more deeply, I began to discern the underlying intentions of its publication. Beyond its appearance as an official record, it functioned as a tool of colonial control—a medium through which the authorities disseminated orders, decrees, and laws to consolidate their administrative power. It served not merely as a source of information, but as an instrument of domination, shaping public perception and defining the boundaries of what could be known, said, or imagined within the colonial state. Through its seemingly neutral reports and formal notices, the Sudanese–Anglo–Egyptian Gazette articulated the logic of authority, order, and obedience that underpinned the colonial enterprise in Sudan.

When Print Became Power

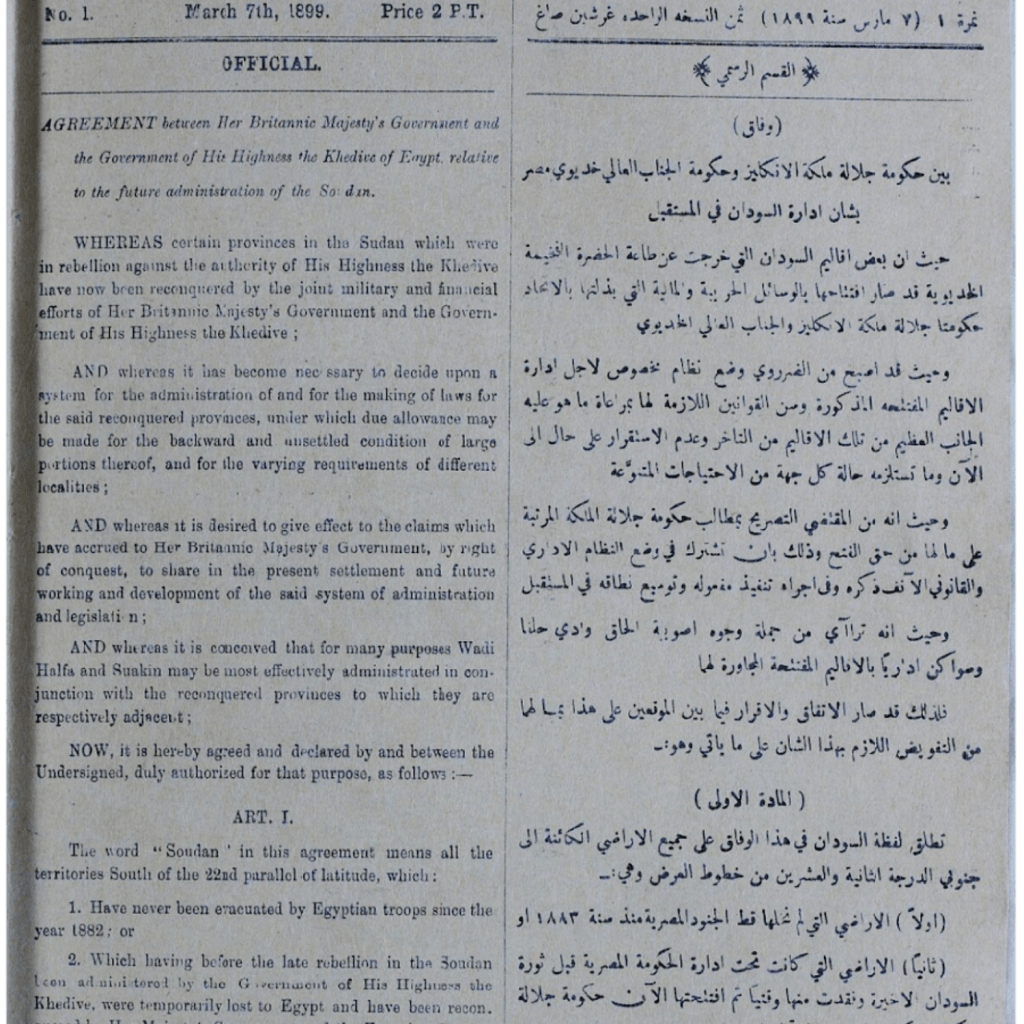

When the first issue of the Sudan Government Gazette published on 7 March 1899, printed in both English and Arabic, marked more than just the start of an official record. It announced the birth of a new colonial order. The document, preserved today in the Durham University Sudan Archive, published the Agreement between Her Britannic Majesty’s Government and the Government of His Highness the Khedive of Egypt relative to the future administration of the Sudan.

The ink on that first page was still fresh when Sudan was declared a Condominium — a territory jointly ruled by Britain and Egypt but in practice dominated by the British Empire. Through this bilingual publication, the colonizers projected authority across a country emerging from the ruins of the Mahdist state. The Gazette was not just a bureaucratic necessity; it was a colonial weapon — a printed voice of control, law and order imposed on a conquered land.

A Tool of Rule

In colonial administrations across the British Empire, the Government Gazette was a key mechanism of governance. From India to Nigeria, it served as the official medium to publish laws, decrees, appointments and notices. In Sudan, it played an even sharper role.

The Sudan Government Gazette became the legal heartbeat of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899–1956), producing a steady flow of ordinances that structured every sphere of life — from taxation and land tenure to the movement of people. It was published first in Cairo and later in Khartoum, signaling the geographic and administrative consolidation of colonial rule.

The first issue itself set the tone. Its language — “Her Britannic Majesty’s Government,” “reconquered provinces,” “the backward and unsettled condition of large portions thereof” — reveals the assumptions of superiority and paternalism underpinning British policy. The text translates violence and domination into the bureaucratic calm of governance. Conquest became “administration” on paper.

Dual Languages, Unequal Voices

The Gazette was bilingual: English and Arabic printed side by side. To the untrained eye, this might appear as a gesture of inclusion. But the structure of bilingualism here was hierarchical. The English version dictated authority; the Arabic version merely followed, often in phrasing designed to legitimize foreign control.

In the Arabic column of that 1899 issue, the same “Agreement” is rendered with deference — a tone emphasizing legitimacy and order rather than occupation. The very act of translating imperial decrees into the local tongue made the colonial state’s language enter Sudanese administrative life, shaping how law and power were spoken.

Printing Empire

Control of the press was essential for the colonial state. The Gazette’s print house, managed by the Sudan Printing Office, also produced textbooks, reports, and propaganda materials. Local journalism was minimal, censored, or co-opted. By contrast, the Gazette enjoyed guaranteed circulation among officials, traders, and missionaries — ensuring that the colonial narrative of progress and civilization reached every bureaucratic desk.

In this sense, the Gazette functioned not only as an instrument of law but as a cultural technology. It standardized political language, introduced British bureaucratic categories, and imposed a uniform calendar of administration — all foundations of modern statecraft built atop colonial power.

Journalism in the Shadow of Empire

While the Gazette defined the official voice, Sudanese journalists and writers gradually began to shape an alternative one. By the 1920s, local presses such as al-Sudan, Hadarat al-Sudan, and al-Ra’id started to emerge, some run by educated Sudanese clerks who had once worked under colonial supervision.

These early papers often echoed official language yet subtly critiqued it; reporting on taxation burdens, education inequality and the slow pace of Sudanization in the civil service. Their very existence was a quiet rebellion against the monopoly of information the Gazette represented.

During the British occupation, media laws were strict: no paper could publish without permission, and censorship extended even to poetry. Still, through coded language and humor, Sudanese writers built a foundation for a national consciousness that would later challenge imperial narratives.

The 1899 Gazette as a Colonial Blueprint

Revisiting that first issue today is like reading a blueprint for the future Sudanese state — but one drawn entirely by outsiders. The Agreement’s opening words, “Whereas certain provinces in the Sudan… have now been reconquered,” erase local agency while declaring the legitimacy of joint Anglo-Egyptian control.

The first article defines “Sudan” as all territories south of the 22nd parallel that had “never been evacuated by Egyptian troops.” In one legal sentence, geography, identity, and sovereignty were redrawn from afar. The Gazette thus became the instrument that legalized conquest, the paper framework on which decades of administrative and racial hierarchies were built.

After Empire

When Sudan finally gained independence in 1956, the Gazette continued to exist, now as a national publication of the Republic of Sudan. But the colonial architecture of bureaucratic language — its tone of distance and command — persisted. Even today, official communication in Sudan often carries traces of this inherited style.

Archival efforts by institutions like Durham University have made it possible to revisit these early issues and read them critically. The digital scan of the March 7, 1899 edition reveals more than just text; it captures the materiality of colonial authority — the fonts, the parallel columns, the calm administrative voice of the empire in ink.

Reclaiming the Archive

For Sudanese researchers, writers, and artists, revisiting such documents is part of reclaiming the narrative power. To read the Sudan Government Gazette not as a neutral record but as a site of domination is to expose how colonial knowledge still shapes statehood, media, and memory.

The challenge now is to transform the archive from a colonial repository into a space of reflection — to use these documents to tell our own stories about governance, resistance and language. As the first Gazette proves, every word that defines “law” or “order” can also reveal the story of how a nation was subdued — and how it can speak again.

Through my work with the group of editors of the Free Sudanese Gazette, I will visit the scanned issues of the Sudan Gazette archive on the University of Durham website whenever possible, with the sole purpose of dismantling colonial narratives and reclaiming the Free Sudan Gazette.

Reference:

Digital archive of Sudan Government Gazettes at Durham University

About the author

Ibrahim Izzeldeen, based in Berlin, is a social worker, writer, and filmmaker. He is an active voice in the Sudanese diaspora through SudanUprisingGermany and works on issues of border justice and the anti-deportation movement.

Leave a comment