As war rages in Sudan, where the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have been locked in a brutal conflict since April 2023, a remarkable grassroots movement has emerged to fill the void left by the collapse of the state and the paralysis of international relief. The Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs)—locally known as Ghoraf Al-Tawari (غرف الطوارئ)—have become the beating heart of a people-led humanitarian revolution.

Formed by the same neighborhood resistance committees that helped overthrow President Omar al-Bashir during the 2018 Sudanese Revolution, the ERRs represent a decentralized, volunteer-powered lifeline for millions of Sudanese civilians. Operating under extraordinary conditions, the ERRs have not only provided clean water, food, healthcare, education, and evacuation services to over 11.5 million people as of December 2024, but have also redefined what humanitarian aid can—and perhaps should—look like.

While traditional humanitarian responses remain constrained by logistics, bureaucracy, and security concerns, ERRs have moved quickly and effectively by drawing on Sudan’s deep-rooted culture of mutual aid, known locally as nafir—a communal call to mobilize in times of crisis. With a decentralized structure that cuts across ethnicity, gender, and political lines, these youth-led networks have created an agile, community-centric model that bypasses the red tape that often entangles international aid.

This ethos, combined with high-risk commitment on the ground, has earned ERRs international recognition. The European Union has commended their work, and in 2025, the Peace Research Institute Oslo nominated the ERRs for the Nobel Peace Prize. That same year, they were awarded two prestigious awards: the Right Livelihood Award and the Rafto Prize for “building a resilient model of mutual aid.”

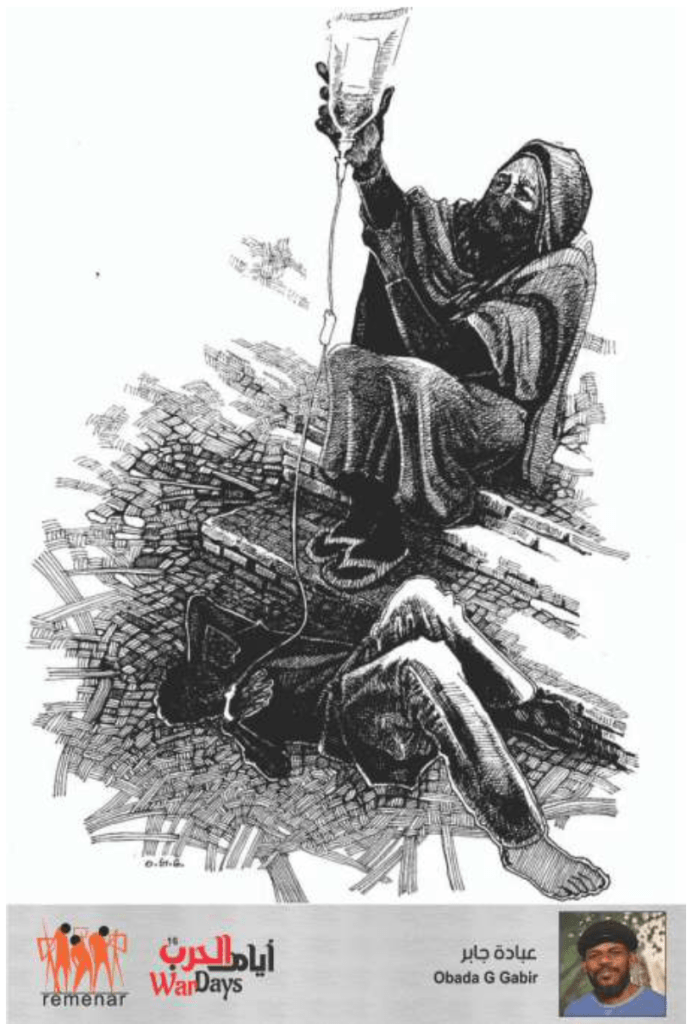

Operating in a war zone has not come without tragic cost. ERR volunteers have been arrested, abducted, tortured, raped, and killed—often targeted by both warring factions. In 2023 alone, three ERR members were killed while evacuating civilians in Al Fiteihab, Khartoum, and two more lost their lives in the Naivasha Market.

Despite these dangers, ERR volunteers—nearly 10,000 across all 18 states of Sudan—continue their work. In some areas, they are the only functioning relief network, supporting hospitals, managing community kitchens, distributing food and water, and offering psychosocial care to survivors of violence, including conflict-related sexual assault.

What sets ERRs apart is not just their bravery or effectiveness—it’s their challenge to the colonial legacy of international aid. ERRs embody what many in the development sector have long called for: a decolonized humanitarian model, where decision-making and implementation lie in the hands of local communities rather than foreign agencies.

Unlike major NGOs and UN agencies, which often rely on expensive, expatriate-heavy structures, ERRs function with local knowledge, unpaid volunteer labor, and direct connections to the communities they serve. For months, they survived solely on funds from Sudanese citizens and diaspora. Eventually, international agencies began providing material aid, acknowledging that ERRs were the only viable delivery mechanism in many regions.

“Even in traditional aid systems, it’s locals who do most of the work,” says John Prendergast, former U.S. National Security Council director for Africa. “ERRs are the purest expression of this principle—no overhead, no imported staff. Just local people saving local lives.”

ERRs are more than humanitarian actors—they are the early architects of a new Sudan. In a country where the state has “abdicated responsibility 100%,” as Prendergast notes, ERRs are proving who can be trusted with public welfare. From sheltering displaced families to ensuring the delivery of medicine and education, these groups are building the foundation for a future Sudanese civil society rooted in compassion, solidarity, and democratic principles.

“This is important preparation for the very basics of governance,” Prendergast adds. “So you turn this kleptocracy upside down, and you actually get back to what governance should be about.”

As Sudan drifts to the brink of collapse, ERRs stand as a symbol of resilience, dignity, and the boundless capacity of ordinary citizens to rise in extraordinary times. Their story is not just about emergency relief—it’s about reclaiming power, agency, and humanity in the face of war and abandonment.

In a world where humanitarian aid is often entangled with geopolitics, branding, and bureaucracy, Sudan’s Emergency Response Rooms offer a starkly different vision: one of radical local ownership, courage under fire, and a politics of care that transcends borders.

And in doing so, they may not only save a nation—but change the future of global aid itself.

The Free Sudan Gazette dedicates a significant part of its content to highlight these great efforts of people on ground and their creative initiatives and help them in raising funds.

Leave a comment