Abullahi Ali Ibrahim

I used to think that Anwar Al-Hadi Abdul Rahman, the Cultural Secretary of the Khartoum University Students’ Union, who organized the seminar on Wednesday, October 21, 1964, had, after more than fifty years, grown weary of monopolizing the heroism of that event on behalf of his organization, the Islamic Movement. But I found, on two occasions, that he was still recounting his memories to the press, accusing the leftists of appeasing the Abboud regime merely because we proposed an alternative to the seminar — a comprehensive student protest in response to the arrest of the Union’s Executive Committee.

I found that this obsession with claiming credit for heroism had taken hold of him so deeply that he even claimed to have led the Executive Committee after the martyrdom of Ahmed Al-Qurashi — even though the President of that committee was his colleague, Dr. Rabee’ Hassan Ahmed.

Anwar presented a muddled timeline of those days that I would like to correct, referring to the account of his fellow Islamist Ahmed Mohamed Shamouq in his book “The Triumphant Revolution: Day by Day” (1968). We will correct Anwar’s following mistakes:

- Claiming that the October 21 seminar was organized outside the scope of the Union (i.e., without approval from the Executive Committee, Council, or General Assembly), and implying that it was solely the work of the cultural association affiliated with the Islamists at the university.

- Ignoring the fact that the Islamists were not fully committed to the seminar as a tool the entire time. At several points, they leaned toward other options — contradicting Anwar’s portrayal of them as unwaveringly committed to the seminar, as if they had foreseen its revolutionary impact. In reality, the seminar was just one of many options being discussed by students and their political factions in response to the arrest of the Executive Committee, all of which carried the spirit of confrontation with the regime. This undermines Anwar’s assumption that any non-seminar suggestion was cowardice or political weakness.

According to Shamouq, when the alternative committee which was formed to replace the arrested Executive Committee (headed by the Islamist Rabee’ Hassan Ahmed, with the Democrat Al-Sheikh Rahmatallah as secretary), there were conflicting suggestions on how to respond to the regime’s actions. The Islamic faction favored continuing with seminars and demonstrations. The Democratic Front warned against acting alone, and suggested coordinating with students in other universities and institutes to launch a joint action against the regime. The Democratic Conference rejected both the strike and protest proposals, limiting the role of students to work on raising awareness among the public. All parties ruled out a strike that could lead to suspending studies and university’s closure.

During this time, the Islamists’ position on the seminar began to shift. Their political bureau met and reconsidered the proposal to continue the seminars. Shamouq described the meeting as “disturbed”, they eventually decided to refer the matter to a higher body, the Executive Bureau of the Muslim Brotherhood, recommending that seminars should not be continued to avoid another confrontation with the regime. The previous clash — the December 5, 1963 strike for university independence — was still fresh in memory. Their assessment was that the students had become isolated, with no response from the public or concessions from the military.

The Islamists’ meeting noted that the university president had promised to preserve the university’s autonomy. They felt they owed him a chance to prove it. They also feared that the government might remove him and replace him with a senior military officer.

Among those who broke ranks on this issue was Anwar Al-Hadi, who insisted on going on with the plan of holding the seminar. He succeeded in convincing the Executive Bureau to move forward with it. When the Union’s Executive Committee met, they considered a proposal for a demonstration, which the Democratic Conference initially rejected in line with their position to halt all political activities and focus on raising awareness among the public. But eventually, both Democratic Conference members were persuaded, and the decision for a demonstration passed unanimously as per Union tradition, to ensure the step’s effectiveness.

The meeting also decided to reach out to students at the Islamic Institute (now Omdurman Islamic University) and the Technical Institute, sending delegates to coordinate a unified response.

Meanwhile, the Union’s cultural associations were pressuring the Executive Committee to continue organizing seminars on the problem of the South. The Union decided to officially adopt the seminars as a leadership responsibility.

There was an atmosphere of anticipation among the students awaiting the Union’s response to the Executive Committee’s arrest. The decision was to organize a demonstration, but this was kept secret. The silence led students to become suspicious of the committee’s inaction and accused it of cowardice, fearing the same fate as the arrested committee.

To contain this negative atmosphere, the committee tasked its president with reading a statement at a student gathering at the main university centre, with copies sent to the Medical Complex and Shambat campus.

However, the committee’s statement did not include any clear steps — whether they were planning to organize a strike, demonstration, or seminar — leading to silence and confusion among the students. In reaction, Omar Al-Siddiq, a member of the Free Students and the Union’s appointed as a speaker to address the Medical students, discarded the statement and launched a scathing attack on the committee itself. This caused internal tensions the committee tried to contain out of fear of division.

The Free Students eventually sided with holding the seminar before any other action (no protest that could hinder it). The Democratic Front and the Democratic Conference opposed the seminar, so the proposal didn’t pass within the Executive Committee. This disappointed the Islamists, who may have encouraged the Islamic Thought Group to submit a request to hold a seminar, which the Union rejected. But the society continued organizing it and invited Mohammed Ahmed Mahgoub, Sadiq Al-Mahdi, and Hassan Al-Turabi as speakers.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s Executive Office later met and decided that holding the seminar on Tuesday, October 20 was premature. They assigned Anwar Al-Hadi to simply inform the Union’s Executive Committee that his office — the Culture Office under the Executive Committee — would be organizing a seminar about the issue of the South on Wednesday, October 21.

The Executive Committee then met in a politically charged atmosphere. Anwar presented his proposal, which sparked intense debate. A vote was held and resulted in a tie: Islamists and Free Students on one side, Democrats and Democratic Conference members on the other, accordingly, the committee decided to refer the matter to the General Assembly.

The Assembly was presented with two proposals: hold the seminar (supported by the Islamists and Free Students), or organize a protest (supported by the Democrats and Democratic Conference). The seminar proposal won. The Democrats’ main objection was that the seminar would take place in an isolation of the people outside the university campus, disconnected from the broader population, turning it into a mere clash with the police.

In the final vote of the General Assembly, the seminar proposal won by a margin of 100 votes.

What Anwar Al-Hadi Never Addresses Is: Who “revolutionized” the Seminar?

Who turned it into what it ultimately became: a confrontation with the police, the killing of Ahmed Al-Qurashi and Babiker Hassan Abdel Hafiz, and the wounding of 22 students? There was no confrontation plan from the Students’ Union. And I don’t believe the Islamic faction — the self-declared masters of this “heroic” seminar — had such a plan either. So who became the fuel for that confrontation?

In this part, I will argue, with evidence, that it was members of the Democratic Front from the Barracks dormitories, who led the confrontation. They may have acted on their own, without instructions from the organization, driven simply by their beliefs and the heat of the moment. I do not recall that there was any directive from the Democratic Front at that time to engage in confrontation.

Let me take you back to the moment the seminar began and how the speakers were arranged.

Representing the Democratic Front — the so-called “cowards” in Anwar Al-Hadi’s opinion — were two individuals: myself (as the note-taker of the seminar), and the late Babiker Al-Haj as the speaker. The Islamic faction had two representatives as well: Anwar Al-Hadi, who introduced the seminar, and their speaker — whose name escapes me as I write. That makes us either an equal in courage or in cowardice.

Actually, it was evidence of our courage and commitment. How could so-called cowards, supposedly hiding behind a protest to avoid attending a seminar they viewed as futile, agree to sit on the panel of that very seminar? That in itself is another form of courage — the courage to yield to the majority’s opinion in a way that does not harm the nation. That is civic commitment.

Anwar Al-Hadi once indicated that some people were offered the chance to speak at the seminar but hesitated — and that he had to assure them that the seminar wouldn’t even last long enough for their turn to come. That sentence struck me. And it led me to wonder: Was that why Babiker Al-Haj, the Democratic Front’s delegate, was put as the first speaker — to let him “burn out” first?

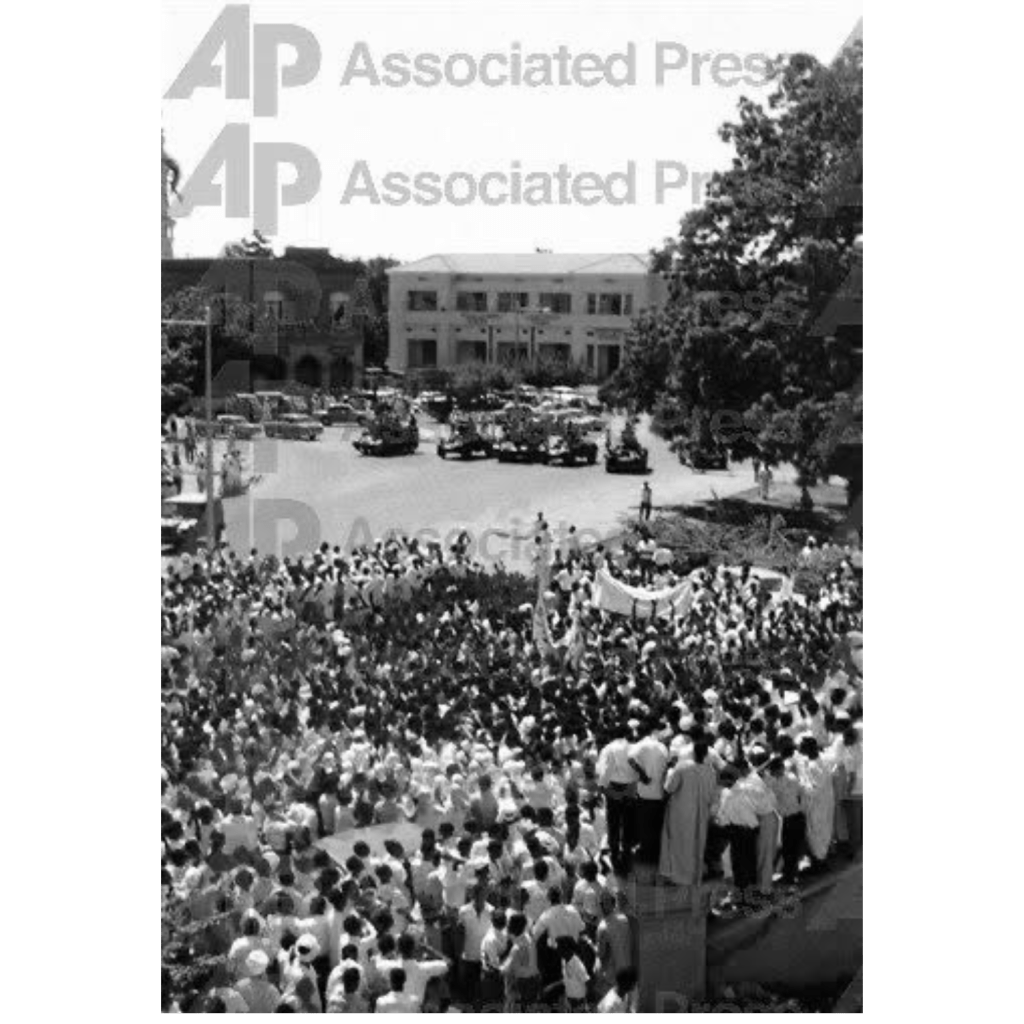

The seminar was held in front of Atbara Dormitory, as it could not be held at the Union Office (which the government had sealed) or in a larger field (which had been flooded, strangely, out of season). Atbara and Al-Gash dorms were among the new, sleek, high-rise buildings, constructed around 1960–61, my first years at the university. We were disturbed by the constant noise and dust of the construction, but I was among the first to live in Al-Gash, and I enjoyed the freshness of the new building’s paint smell and texture.

I took my seat on the platform next to our comrade Babiker Al-Haj Babiker, who was from Gudwab, near Berber. He was the leader of the Democratic Front and its top Union candidate. A committed communist from Aroma, he had been mentored in the 1950s by Al-Gizouli Saeed, the then the Communist Party’s secretary in the Gash region of eastern Sudan. He married while still a student and named his firstborn Qassim, following the example of the exemplary figure.

I never knew a man of greater integrity, intelligence, calm demeanor, and eloquence. I cherished our friendship during the years 1963–1964, when the university suspended us (and others from the Union) for a year due to a protest that erupted during a graduation ceremony attended by African university presidents. We both worked as teachers during that year — I in Omdurman’s Al-Jumhuriya School near Hamad Al-Nil cemetery, and he in Khartoum 3. We were inseparable. May God have mercy on him and bless his children — the calm, composed, and dignified man.

I opened my notebook after Anwar introduced the seminar. The first speaker was our comrade Babiker Al-Haj, and I began transcribing his speech. He hadn’t spoken for long before the police raided the seminar and ordered us to disperse. Someone from the Union’s Executive Committee — perhaps even Anwar himself — asked the students to disperse in an orderly manner.

I closed my notebook and headed toward my dorm via the Baraks gate, wary — as communists often are — of being arrested before I reached safety. I ducked into a random room in one of the dorms and asked the occupants to hide the seminar notes until the situation became clear. Then I left. I only learned what happened after the seminar from the Khartoum Hospital and its morgue, when news spread of the victims of the confrontation. That notebook still haunts me — the written record of a seminar where bullets spoke, and blood spilled.

But it seems the atmosphere in the Barracks dorms, where the seminar was held, was different from that of us final-year students in the outer dorms. I lived in White Nile dormitory, now the Faculty of Law. I later learned that a group of Barracks students had been preparing for a clash with the police. Perhaps they were angered by their earlier dispersal during the October 10, 1964 seminar. And surely the arrest of the Union’s Executive Committee on October 15 had strengthened their resolve to fight back — blow for blow.

They had gathered bricks and construction debris to defend against the police. As mentioned earlier, the students had accused the Executive Committee of inaction after the arrests — particularly in the wake of the well-known rebellion of Eng. Omar Al-Siddiq, who addressed the students without the committee’s approval when he sensed their eagerness for confrontation with the regime.

“Your seminar — but who carried it through?”

We mentioned that Professor Anwar Al-Hadi Abdul Rahman, Secretary of Culture in the Khartoum University Students’ Union — during whose tenure the October 1964 Revolution erupted — believed that our proposal in the Democratic Front to organize a protest, contrary to the Islamists’ proposal to hold a seminar, was an act of cowardice. In his view, we had grown weary of the struggle against Abboud’s regime and leaned towards a strategy of appeasement, entering his institutions, undermining them from within, or trying to seize control of them.

Yet you won’t find him demonstrating the courage or organizational prowess he claimed, beyond proposing and organizing the seminar, without preparing for the possibility that it might explode the way it did. Neither the Union nor the Islamic faction had a Plan B — no clear course of action for the students once the seminar, which the state was clearly targeting (as it did with the seminar of October 10), was attacked.

When the police stormed the seminar, all Anwar did was urge the students to remain in place. And when the police became more aggressive, he simply asked them to secure the female students in a safe spot. That was it. After that, Anwar — along with other senior students — returned to their dormitories along University Avenue, far from the Barracks area.

Had it not been for a group of students from the Barracks who rose to the occasion, Anwar’s seminar — which he held up as a testament to the Islamists’ courage and everyone else’s cowardice — would have been just that: a seminar and nothing more. Just another event that dispersed — “and that was that, folks!”

If anyone deserves credit for courage that night, it’s that group who “liberated” the abandoned seminar from the grasp of the police. I’ve always suspected that the core of that group came from the Democratic Front — and that they acted on their own initiative, without direct orders from the Democratic Front secretariat.

I knew that some of our comrades were martyred or wounded in that incident: Ahmed Al-Qurashi, Abdullah Mohammed Al-Hassan, Al-Wadi’ Al-Sanousi, Mohammed Faiq. But I counted them among the many participants and never questioned my dear late comrade Abdullah Mohammed Al-Hassan about the heroic stand those comrades took.

More recently, however, testimonies have emerged indicating that a group of our comrades from the Democratic Front in the Barracks had made a pact to carry the seminar through to its logical conclusion: confrontation with the police. That is something Anwar cannot claim for the Union or the Islamic faction — nor even for us, officially, in the Democratic Front.

About the author:

Professor Abdullahi Ali Ibrahim is a Sudanese prominent historian, writer and academic based in the US

Leave a comment