By: Ahmed Adam*

In the heart of Melbourne, on Spring Street near Parliament House, stands a monument that draws attention because of the sheer space it occupies, even as its history and significance remain largely unknown to most passers-by. The statue commemorates the British general Charles Gordon, who never set foot in Australia, yet whose death in Sudan reverberated across the imperial world, including the Australian colonies. This monument can be understood not simply as a memorial to a general who served the British Empire in China, India, and Sudan, but as part of an imperial geography that linked Melbourne, London, and Khartoum within a shared colonial economy and political imagination.

Gordon was sent to Sudan to defend imperial authority during the Mahdist uprising, at a moment when British confidence in the permanence of its global colonial reach appeared unshakeable. Yet by early 1885, Gordon found himself isolated in Khartoum, besieged by forces resisting imperial rule. In mid-January, he sent one of his final telegrams to London, warning that he would be killed if reinforcements did not arrive. Ten days later, on 26 January 1885, Mahdist forces liberated Khartoum and Gordon was killed. Across Britain and its colonies, this event was experienced not merely as a military defeat, but as a rupture in imperial authority and a sign that empire could be resisted and forced to fracture at its edges.

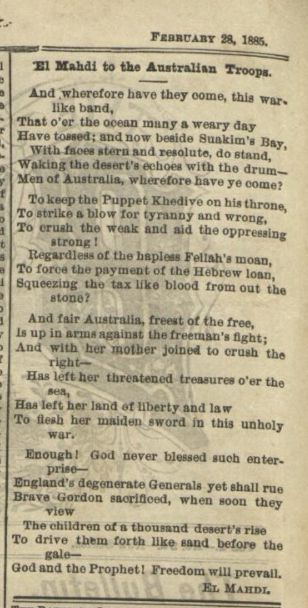

The shock travelled quickly across the globe, though it was not felt evenly. While Britain and its colonies mourned Gordon’s death as an imperial tragedy, others read the event very differently. In parts of Europe, including Ireland, the defeat of the empire was openly celebrated, and poets wrote of Khartoum as a moment of imperial humiliation. These divergent responses reveal an imperial world already beginning to crack under the pressures of resistance, shared struggle, and refusal. Within weeks, the colony of New South Wales dispatched a military contingent to Sudan, the first overseas deployment of Australian colonial forces, transforming a distant imperial crisis into a local event. The departure of the troops was anything but subdued. The day was declared a public holiday in Sydney.

Thousands gathered near the harbour to farewell the soldiers, as streets and pavements filled in a collective ritual of imperial belonging. Newspapers described a city overflowing with flags, speeches, and cheers, as though everyone had surged toward the centre, shouting encouragement while the troops boarded their ships. The chant that echoed through the crowd, “Go and give the Mahdi what he deserves,” captured the ease with which distant violence was embraced as a moral duty. Militarily, the New South Wales contingent achieved little and returned without altering the course of the conflict. Yet through a small number of artefacts preserved at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, the campaign endures as a symbolic precedent, an early rehearsal of Australia’s participation in foreign wars fought in service of larger imperial powers.

What began as loyalty to the British Empire would be reconfigured in the twentieth century through alliance with the United States, marking a continuity expressed not through sovereignty but through dependency. This continuity is most clearly materialised in the establishment of Pine Gap, one of the most strategically significant United States military and intelligence installations outside American territory. What began as colonial allegiance to Britain thus reverberates through contemporary geopolitics, revealing how distant wars, foreign alliances, and local infrastructures have long been entangled with Australia’s role within global imperial networks.

Colonialism is not a closed chapter, but an ongoing condition. The deployment of military force, whether in 1885 or today, carries consequences that exceed strategy and statecraft. In Australia, the same structures that enabled participation in overseas wars also underpinned the control of First Nations lives and the dispossession of their lands. Acknowledging these continuities does not collapse distinct histories into a single narrative, but instead illuminates the varied ways empire exercised its expansion and domination, while also foregrounding Indigenous resistance, both in Australia and in Sudan, whose endurance stands as a lasting reminder of what empires can never fully erase.

Reading 26 January 1788 alongside 26 January 1885 reveals how the empire operated across the globe, producing invasion at one end and crisis at another. In Australia, the same decade witnessed an intensification of colonial control over First Nations peoples. During the 1880s, land dispossession accelerated, reserves and missions expanded, and governments increasingly regulated movement, labour, and family life, entrenching lasting harm and exclusion. The resistance of First Nations peoples in Australia and anti-imperial struggle in Sudan thus unfolded within the same imperial world, experienced unevenly, remembered differently, yet structurally connected. Together, these contexts show that resistance and survival were not exceptions, but central features of an imperial system built on domination and control. From this shared ground, we can trace imperial cartographies not only through battles and treaties, but through the everyday strategies of those who endured, adapted, and refused erasure from history.

The absence of the Sudan War from Australian public memory is not accidental. It occupies an uncomfortable place within national narratives that prefer to imagine Australia either as an innocent, isolated outpost or as a reluctant participant in empire. Remembering the New South Wales contingent requires acknowledging that Australia’s formation was entangled not only with violence against First Nations peoples at home, but with imperial violence abroad. Invasion was normalised as settlement, while imperial war quietly faded from view. What remains visible are monuments stripped of their context.

The need to excavate this distant memory becomes even more urgent in light of contemporary debates surrounding Australia’s role in the current conflict in Sudan. Recent public and parliamentary discussions have raised concerns about Australia’s arms export regime, including approvals for military exports to the United Arab Emirates, a state shown to be involved in the Sudanese conflict. While the mechanisms differ from those of the nineteenth century, the underlying pattern remains familiar, distant violence, economic interests, and strategic alignment with dominant capital.

Remembering Australia’s forgotten histories, from the New South Wales contingent to contemporary complicity, is not an exercise in moral equivalence or simple reckoning. It is an insistence that these histories are interconnected, and that their erasure serves particular interests. The task is not to inherit the maps drawn by the empire, but to learn how to forget them. Against imperial calendars and imperial crowds, movements of resistance point toward a different future, one organised not through domination and territory, but through endurance, solidarity, and the unfinished work of peace.

* Ahmed Adam is an artist whose practice spans film, photography, writing, and African drumming.

Leave a comment