Excerpts from a book with the same title by Dr. Muhammad Mustafa Musa

Introduction by: Professor Abdullah Ali Ibrahim

Published by Dar Al-Musawarat for Printing and Publishing – 2019

Chapter Six: The Global Echoes of the Liberation of Khartoum1885

As 1885 drew to a close, cold winter winds filled the flags of the Mahdi Revolution planted in the soil of the capital (Khartoum), liberated for the first time in sixty-five years of foreign occupation. Far from Sudan, whose soil was boiling like a cauldron under the feet of the British, the British Isles were weighed down by bitter news when, that same month, reports came in of Sudanese victories over their invading forces. The news of Gordon’s death, coupled with the resounding defeat suffered by the armies of the empire on which the sun never sets, struck like a thunderbolt on safe and secure ground. The overwhelming grief rushed to invade the gates of Buckingham Palace, despite the fierce guards, shaking the throne of Queen Victoria, whose heart was set on the expected victories of her army sent to rescue Gordon. In the same context, there is nothing more expressive of the above than what Lord Ponsonby, the Queen’s private secretary, wrote in documenting those moments when Her Majesty received news of the Mahdist victories. Let us leave it to British historian Robin Neillands to convey the entire scene in the words of the royal secretary:

“The queen was in such a bad state after the fall of Khartoum that she looked like a patient lying in bed. She was just getting ready to go out when we received a telegram with the news. When she came to my private residence, her face was pale. There I found my wife, who was horrified by the sight of Her Majesty in that state, and the queen was telling her, while trembling: ‘It’s too late!’ … Neillands then goes on to say: The Queen was not alone! When news of Gordon’s death reached London … mourning spread throughout Britain, flags were lowered, and that day was declared a national day of mourning. Soon, the general sadness turned into overwhelming anger directed at British Prime Minister Gladstone.

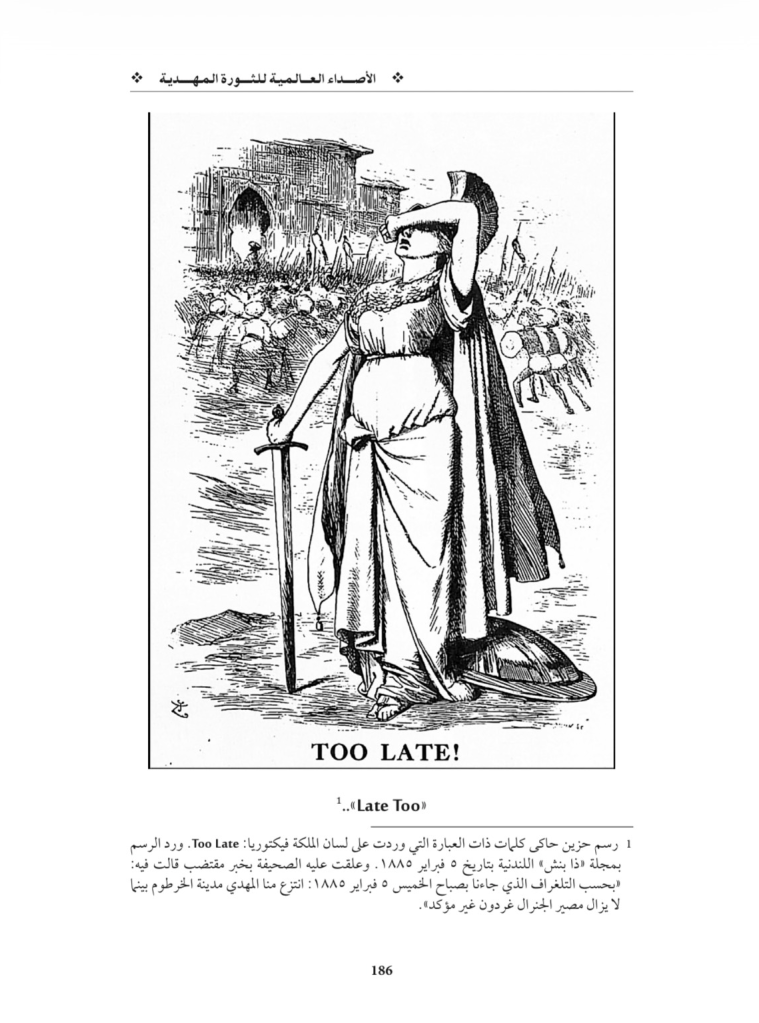

A tragic, allegorical cartoon inspired by the phrase spoken by Queen Victoria: “Too late.”

The cartoon was published in the British satire magazine “Punch” on 5 February 1885.

Deep concern dominated the pages of important British newspapers such as The Morning Post in London. That renowned newspaper wrote in a tone steeped in lamentation about the need to respond to the Mahdist revolution’s insults to Britain’s dignity in Sudan with a new military strike. To emphasize the importance of this, the newspaper discussed how the victories of the Sudanese revolution could undermine British colonial control over various parts of the world, noting at the same time that this devastating impact could destroy Gladstone’s government itself. It said:

“The enormous disaster that has befallen us in Sudan will have far-reaching consequences that make us unable to believe that the current British government will remain in power for more than a week after the next parliamentary session. We cannot retreat before the Mahdi and his hordes without sacrificing our control over Egypt and without shaking the foundations of our empire in India. Since we have become involved in this conflict, we must see it through to the end. Since we have already gone to Sudan, we must not leave until we are victorious.”

What the aforementioned London newspaper called for remained in the realm of wishful thinking, given the reality of the military situation in northern Sudan. The commander of the retreating British campaign, his forces heavy with wounds, soon received a letter full of confidence from al-Mahdi—after he had liberated Khartoum—to all the soldiers of the British campaign, demanding that they surrender, as he had done before with Gordon. The letter read:

“The soldiers of God have come to you, and you have no power to fight them, but out of compassion for you, we have ordered them not to fight you until after this letter reaches you and you proof your refusal to respond, and not to harm you or infringe upon any of your rights if you surrender, except confiscating your military uniform, weapons, and ammunition. If you surrender, you will have the protection of God and His Messenger and the protection of the servant of God.” He then added:

“Otherwise, if you disobey, we will not accept any action from your side, and you will see what will happen to you.”

However, Lord Wolseley, who fought hard to put on a mask of false pride in the face of everything that had happened, was unable to hide his mounting anger and bitterness, at least among his close circle of friends. A few days after receiving the Mahdi’s letter, he wrote to his wife, Louisa, acknowledging the trap the Sudanese revolution sets on them on all fronts, saying:

“The Mahdi has triumphed… and here we all are… looking like fools!”

Wolseley’s initial assessments, which were certain of his inevitable victory over the Sudanese resistance on their own soil, were reversed when he asserted that any British military operation to advance against the Mahdist forces now with the aim of recapturing Khartoum from their control would be “the most dangerous military operation in Britain since the famous Battle of Waterloo against Napoleon’s French forces.” .” Wolseley requested significant military reinforcements from London, which the British Parliament estimated would cost approximately four and a half million pounds sterling. However, British Prime Minister Gladstone, stunned by the victories of the Mahdist revolution, sought to put an end to this losing confrontation when he addressed Parliament, saying: “Is there any moral justification for wasting the lives of such a large number of our troops in the current situation of our empire and the urgent need for those troops? We are fighting against a harsh environment in Sudan, and I cannot hide from you my fear of becoming involved in fighting a people who are striving for liberation. This has been clearly demonstrated by what has happened in this country.”

The “Bury and Norwich Post” newspaper reported:

“There is not a single observer monitoring the movements of the lobbies influencing the decisions of the British Cabinet who would harbour the slightest doubt that last Monday’s debates clearly showed that the determination to crush the Mahdi in Khartoum has ended in complete death, similar to the death that befell Julius Caesar. However urgent it may have been for us to destroy the Mahdi’s forces in the previous month, the necessity is even greater today. But the British government ministers have discovered that these operations against the Mahdi will be costly and protracted and, more importantly, not unanimously supported by their own supporters. Consequently, all their heroism has evaporated. These ministers, who had rashly decided to inflict a crushing defeat on the Mahdi in Khartoum, were now anxiously considering how they could flee before the Mahdi would crush them.

The “Pall Mall Gazette” reported:

“It is rare for the English Parliament to meet under skies darker than those of today.”

“The moment Khartoum fell, as had been predicted by the many warnings received by the British government since the previous summer, the situation there underwent a major transformation. As a result, the Mahdi went from being a mere rebel against our influence in Central Africa to a recognized leader of all the Arab tribes in the Nile Valley. We must remember what General Gordon wrote with his own hand when he said: “The moment the Mahdi extends his influence over Khartoum, the task of crushing him will become extremely difficult. Nevertheless, the security of Egypt may compel you to carry out this task). Here, the Mahdi confirms all of General Gordon’s fears. Instead of sitting contentedly in Khartoum after the city gates were opened to him because of collusion, he is taking the initiative and advancing toward us. At this very moment, it is said that he is advancing toward our meager army with 60,000 of his victorious troops, consisting of Sudanese Bedouins, whom he himself has taken command of. The whole situation has taken on a completely revolutionary character.”

“In all the cities of Egypt, there will be a wave of public sentiment that they can do what the Mahdi did in Sudan. Just as he expelled the invaders and infidels, they may be able to accomplish what he did. The Mahdi has stirred up a dangerous state of unrest against us in the Arabian Peninsula and Syria. Leaflets to this effect have already been distributed in Damascus, calling for a revolution against the Turks in order to expel them from that country. If all of eastern Sudan submits to the Mahdi, it is possible that all the Arab tribes on both of the Red Sea coast will take up arms for the same purpose. If nothing is done in this regard, it is very possible that the Mahdi’s victory over us will lead to the reconsideration of the matter of the East as a whole..

Echoes of the Mahdist Revolution’s victories in British economic circles:

There is no doubt that the losses suffered by the British as a result of the Mahdist Revolution’s victories over them were not limited to the military and political spheres alone. The British press recorded extensive details of how the battle to liberate Khartoum and the ensuing turbulent events shook the British stock market and the resulting economic losses that spread to other financial markets under their colonial influence, such as Egypt. Such economic setbacks were not long in coming after Al-Mahdi’s triumphant entry into Khartoum, with objective expectations forming in the collective English mind that his forces would advance north to defeat the remnants of the invading British forces and then invade Egypt from the south, threatening their colonial interests in the region. In this regard, the London Daily News wrote:

“After the sad news arrived from Khartoum, all financial markets fell except for Grand Trunk Railways, which was the only one to record an increase. The Egyptian financial markets suffered the heaviest losses, of course, while the decline in British government capital was one of the most serious general features in this regard. Although the British losses were not as heavy as the Egyptian losses in percentage terms, the decline in the value of British bonds amounted to three million pounds sterling in terms of sale value, while Egyptian bonds suffered a decline in sale value equal to half that suffered by British bonds. These very wild estimates at this particular time came in line with the current difficulties and the accompanying economic costs, which in turn affected the English interest rate.

The London-based newspaper “The Morning Post” pointed to the severity of losses in British financial markets after what it called “catastrophic news from Sudan about the fall of Khartoum.” However, it mentioned that there was a recovery later in this regard, despite confirming that trading prices remained at their lowest level at best. The same newspaper pointed out that trading on other global financial markets also remained weak, while British defeats in Sudan cast a shadow over trading in shares of the English Railway Corporation in London and northwestern England, as well as on the English financial market in Crystal Palace, which suffered the heaviest losses, leading to the deposit of £100,000 in gold to cover the gap.

To complete the objective assessment of the losses incurred by the Mahdi’s resistance to the invading British forces, it is important to give ample space to the figures that capture the facts with the appropriate accuracy. In this context, we find that several English sources have estimated the total amount spent by Queen Victoria’s government and her Prime Minister Gladstone to equip the British army sent to Sudan to confront the Mahdist revolution and rescue Gordon, jumped from 300,000 pounds sterling at the beginning of the campaign to 7,236,000 pounds sterling at its end.

If we consider that the British national income for that year, 1885, was approximately £77 million, the numerical equation here confirms that the losses incurred by the Mahdist revolution to the British economy as a whole in 1885 amounted to approximately 10% of the British national income for that same year. More specifically, it is clear that British government spending on the Sudan war exceeded 37% of the total budget allocated to the British Royal Army in 1885, which amounted to £19,355,000.

Ireland… Irish nationalists celebrate the liberation of Khartoum:

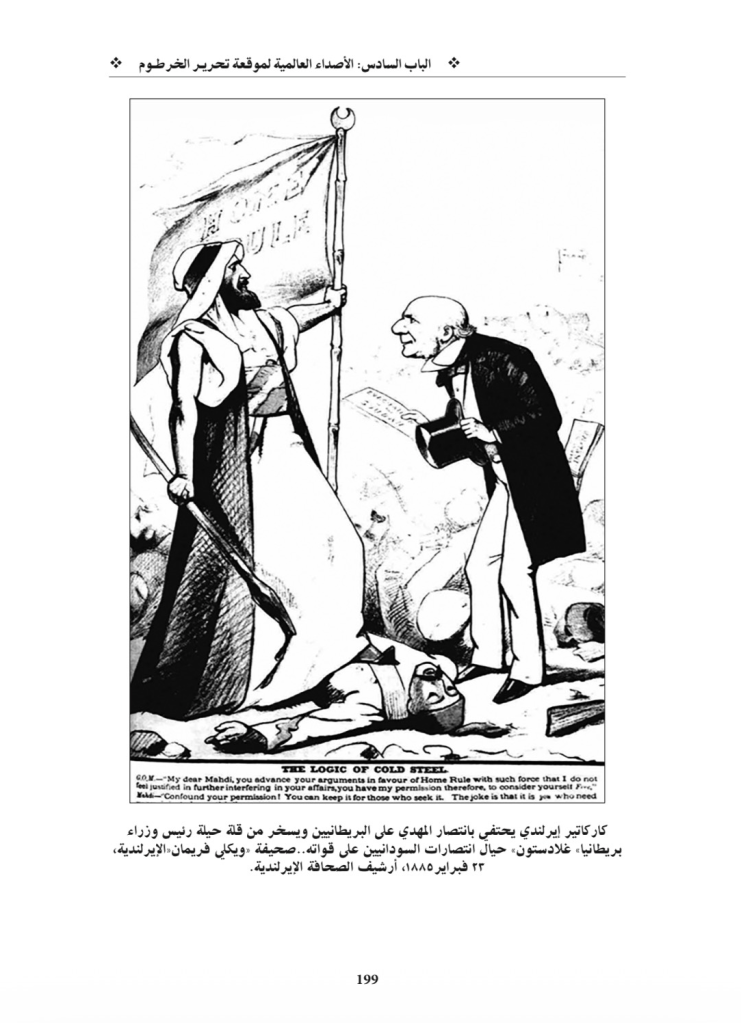

On the other coast opposite England, Irish nationalists eagerly awaited news of the Mahdist revolution, which was confirmed by many different sources. It is not difficult for the inquiring mind to understand the source of this enthusiasm for the echoes of the Sudanese victories there, given that the Irish island had been under British occupation for nearly 800 consecutive years, which were not without violent popular resistance to colonial influence, albeit without complete success. Irish nationalists, whose voices of rebellion against Queen Victoria’s crown had grown louder at the time, turned to various creative means to express their celebration of the Mahdist revolution’s victories over an enemy that most of them considered to be the common enemy of peoples aspiring to freedom. Irish nationalist artists excelled in using satirical cartoons to express, in their own creative way, their admiration for what had happened in Sudan. For example, the Weekly Freeman newspaper, known for its Irish nationalist leanings, published a satirical cartoon on February 23, 1884. The cartoon shows British Prime Minister Gladstone bowing before the Mahdi, who appears tall and proud, carrying a spear and a banner reading “National Rule.” The cartoonist included a short dialogue between the two leaders. In it, Gladstone addresses the leader of the Sudanese revolution from his bowed position, saying: “My dear Mahdi… Your argument for the independence of your country was so powerful that I can no longer find any justification for interfering in your internal affairs and therefore accept my decision to grant you your freedom.”

However, the artist himself responded sarcastically through Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi, a response that must have been swallowed by the English newspaper’s readers with a grain of salt similar to his hypothetical words. He replied as follows: “Keep your decision for those who need it… We don’t need it… Now you are the ones who need us to accept to allow you to leave for your homelands!”

An Irish caricature celebrating the Mahdi’s victory over the British, mocking the helplessness of the British Prime Minister, Gladstone, in the face of the Sudanese victories over his forces.

Newspaper: The Weekly Freeman

Date: 23 February 1885

Source: The Irish Newspapers Archive

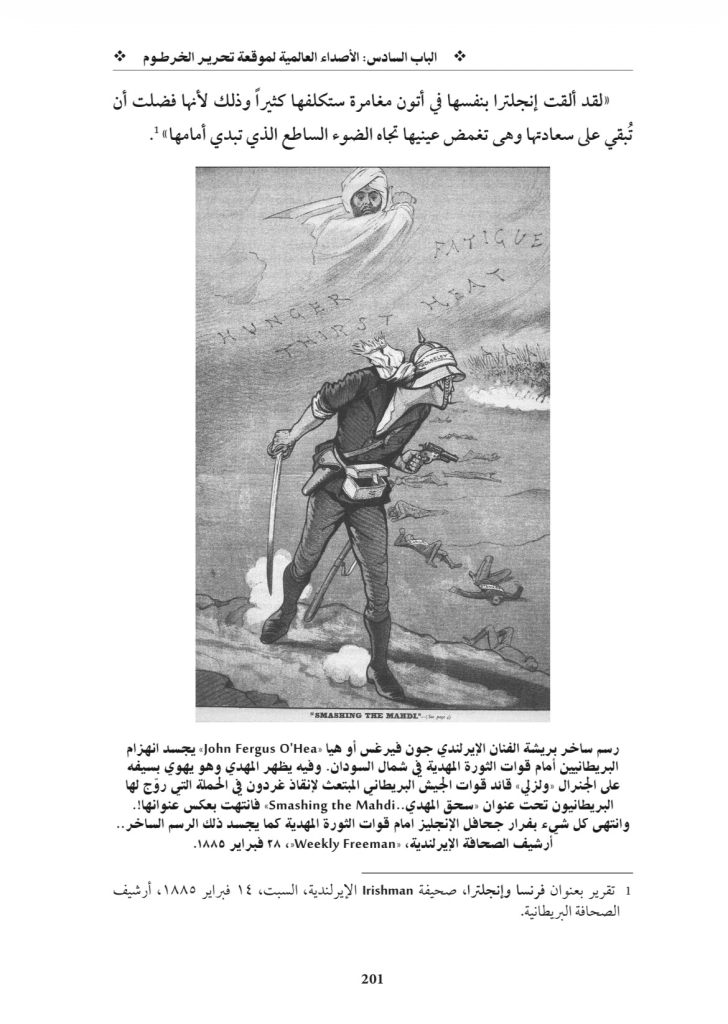

Only five days passed before the publication of that cartoon in Weekly Freeman before the well-known Irish cartoonist John Ferguss O’Hea followed suit with another drawing in the same newspaper, in which he exaggerated his mockery of the calls by British officials to crush the Mahdi’s revolution, highlighting the irony of the situation when British forces were forced to retreat in the face of the Sudanese revolutionary forces in the northern desert. This was clearly illustrated in the cartoon, which shows Wolseley, the commander of the British rescue campaign, running away, leaving behind the bodies of his generals who had been killed by the Sudanese, such as Stewart and Earl, their bodies lying in the desert sand. Wolseley appeared to be overcome with panic, pursued by Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi with his sword, which he was about to plunge into his neck.

A satirical drawing by the Irish artist John Fergus O’Hea, depicting the British defeat in front of the forces of the Mahdist Revolution in northern Sudan. In it, the Mahdi appears as a ghostly figure hovering in the sky, holding a sword on which the words “Hunger,” “Thirst,” “Fatigue,” and “Heat” are written. The British army command had been sent to rescue Gordon during the British campaign under the title “Smashing the Mahdi.” But the campaign ended in complete failure and the English army collapsed in front of the forces of the Mahdist Revolution, just as this satirical drawing illustrates.

From the The Irish Newspaper Archive , Weekly Freeman, 28 February 1885.

The writer and playwright known for her nationalist views, Lady Augusta Gregory, considered the Mahdist Revolution in Sudan to be revenge for the Irish people for the suffering they endured as a result of the British occupation of their lands. Lady Gregory published a pamphlet about these events with hard-hitting headlines such as “Here we are destroying the British beast: the Mahdi is avenging us overseas… and we are destroying the same beast with dynamite at home.”

In the Irish press, the “World Irish” newspaper cleared the dust from the events in Sudan and reported on the liberation of Khartoum by the Sudanese forces, devoting its entire front page to news from Sudan. On February 7, 1885, the newspaper wrote: “The valiant Sudanese revolution deserves the full sympathy of all friends of freedom all over the world.” All this coincided with multiple reports published by various Irish newspapers such as the Irish American”, the “Journal Freeman”, and the “Irishman”, most of which agreed, according to “Irish historian Niall Weelehan, that the Mahdist Revolution’s victories over the British would weaken the entire British Empire.

The editors of “The Irishman” wasted no time in engaging in a deep analytical reading of the repercussions of the Sudanese Revolution’s victories in various parts of the world, including France and the British Empire itself. The newspaper’s issue published on the morning of February 14, 1885, featured a lengthy report on recent events in Sudan. In a unique way, “The Irishman” drew on scattered opinions in which it approached the details of events as closely as the French press, which celebrated without exception the victories of the Sudanese revolution over the British. Among these was a report published by “La République française”, which sharply criticized British global policy, which made their empire resemble an ostrich burying its head in the sand so as not to hear any news that might offend it. The French newspaper portrayed the Mahdi’s victory over Britain as a bright light that it would be possible to ignore or forget.

Leave a comment