By: Dr. Mohamed El-Wathig Elgerefawi

Introduction

First: The Importance of Deconstructing and Liberating the Concept of Mahdism

It is extremely important, if we seek to engage in a new reading of Mahdism through a different methodological approach, to clearly distinguish between the concepts associated with Mahdism: The Mahdist propagation and its Imam, The Mahdist revolution and its leader, and The Mahdist state and its interactions.

For the purposes of research and analysis, it is useful and indeed necessary to differentiate between these components and to disentangle them from one another.

Although the Mahdist call was present in the Imam’s daily activity, conceptually linking it directly to the Mahdi’s revolutionary movement is harmful, as it creates serious difficulty in proposing answers capable of withstanding methodological scrutiny.

Second: The Necessity of Differentiation in Approaching Mahdist History (Propagation vs. Revolution)

In dealing with the history of Mahdism, a fundamental question immediately arises:

Do we approach Mahdism as a religious propagation (inseparably linked to its founder), akin to divine revelations? Or do we approach it as an action-oriented process, tied to behavior, a program of action and its interaction with society, its movement and effectiveness?

This paper advances a concise conclusion: in our attempt to present a different vision through a new reading of Mahdist history, Mahdism should be approached within its procedural, dynamic, and active framework, and through an objective reading of the revolutionary activity of its leader.

The difference in historical time and the absence of subjective data related to the central leader make it imperative to rely on reproducing the role played by Mahdism as an interactive movement. Accordingly, the Mahdi should be reintroduced as a national leader around whom people gather at that time, rather than confining the revolution dynamics by enclosing it within the dialectic of Muhammad Ahmad’s Mahdisim.

We must not imprison the revolution within rigid conditions or remain captive to debates over the applicability of Mahdist prerequisites. It must be acknowledged that Muhammad Ahmad as “the Mahdi” is absent and historically concluded, yet his revolutionary program remains present, adaptable to the requirements of time and place, open to disagreement, modification, or even transcendence as circumstances demand.

After all, this is a worldly matter: a philosophy of governance and administration governed by contextual realities.

The Ansar may view Mahdism as a belief system through the lens of its mission, and translate that mission’s program into reality through the tools of da‘wa. Meanwhile, all Sudanese may view its leader through the lens of national leadership, invoking his dynamic role and effective revolutionary management.

Conceptual Foundations

First

Everyone seeks a history in a world that increasingly values culture and its components. History, in this sense, is one of the most important elements. One scholar remarked that some attempt to fabricate a history out of nothing, so what of us, whose history is deeply rooted?

Our methodological problem, however, lies in emotional engagement with history through projections, suspicions, biases, and preconceived judgments.

Second

We are not capable of changing historical events. Yet we possess the full right to re-read them. Not to reproduce them, but to understand our present and anticipate our future.

Third

Despite extensive criticism of the historical method for its inability, on its own, to produce generalizable conclusions—necessitating integration with social or political scientific methodologies—Ibn Khaldun overcame rigid historical approaches and encouraged studying the core of history (para-history).

This approach does not stop at documentation but delves into causes and consequences by examining internal and external factors: the subjective characteristics of key actors, as well as social, economic, and historical contexts.

Fourth

Avoid projecting contemporary standards onto history. Events must be judged by the standards, conditions, and data of their own time. Judging history by present day criteria constitutes injustice and a violation of scientific study.

Chapter One: Challenges in Studying the Biography of Imam al-Mahdi

Numerous challenges arise when studying the history of the Mahdist Revolution, particularly the biography of Imam al-Mahdi. These challenges are both methodological and source-related.

Methodological Challenges

Many studies of the Mahdist Revolution have relied on a purely documentary historical method, without presenting comprehensive analyses that account for all objective factors of influence and interaction.

Even those studies that analyzed the causes of the revolution and its success limited these causes—despite their objectivity—to the violence accompanying Turkish rule, particularly al-Defterdar’s retaliation for the killing of Ismail, son of Muhammad Ali, alongside oppressive taxation and colonial administrative practices.

Regarding its success, most studies attributed it primarily to the weakness of Turkish administration, loss of control, and underestimation of the revolution in its early stages.

Although these studies portrayed the Mahdi as the leader of the revolution within a chronological narrative, they failed to dedicate chapters to his personal capacities in mobilizing and leading the revolution, his ability to integrate all surrounding factors into a cohesive force that highlighted his leadership abilities which led to these triumphant successes.

Methodologically, studies fell into two opposing camps:

- An antagonistic approach, seeking to deny the Mahdi’s claim and thereby invalidate the entire movement.

- A defensive approach, striving to prove his Mahdism as the foundation of his success.

Both approaches harmed the man’s historical legacy, diverting scholarly attention away from his personality and leadership skills toward theological debates over Mahdism.

Another challenge lies in the transformation of the Mahdi from a national symbol into a political symbol—historically and in contemporary times—first through colonial propaganda, then through regional polarization following his death, and later as a symbol of the Ansar sect and the Umma Party.

All of this diminished his status as a national figure.

Therefore, any reading of his biography must not follow a mere chronological narrative but adopt an objective analytical approach, linking premises to outcomes and treating events as precursors to historical results.

Source Challenges

Scarcity of Studies

Professor Qasim Osman Nour noted that in 1981, while preparing for the centennial celebration of the Mahdist Revolution, he found forty books on Gordon at the University of Khartoum Library and not a single book devoted to the biography of Imam al-Mahdi.

Oral Sources

A major challenge is the absence of sources on al-Mahdi’s life before the revolution. Most available material is oral narration, which has influenced many studies that rely on popular storytelling marked by exaggeration and idolizing narratives.

Despite documentation in footnotes, such accounts remain secondary sources and weaken methodological research study.

Intelligence and Military Documents

Another challenge involves documents produced in the form of intelligence and military reports, often written in hostile wartime contexts.

Chapter Two: Imam al-Mahdi’s Philosophy on Managing Change and Diversity

Personal Capacities

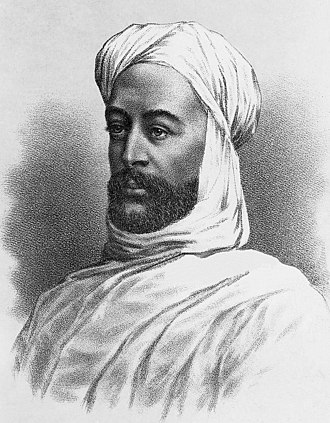

After proclaiming Mahdism and winning the Battle of Aba Island, Muhammad Ahmad assumed a dual responsibility: intellectual (defending his idea) and military (leading fighters).

Here, his leadership genius emerged in his exceptional ability to logically connect intellectual and military realities.

Charisma

Contemporary observers—both allies and adversaries—acknowledged his charisma.

Accounts from missionaries, intelligence officers, and Sudanese historians describe his powerful presence, eloquence, and ability to emotionally mobilize followers.

Comprehensive Knowledge of Sudan

Through his work in trade, travel, religious teaching and dissemination of the Sammaniyya order, Al-Mahdi traversed Sudan extensively, granting him deep understanding of the land and its people.

Strategic Military Organization

Al-Mahdi adopted a sophisticated military strategy inspired by the Prophetic model, including:

- Secret phase of preaching

- Strategic migration

- Selection of battlefields

- Guerrilla warfare

- Efficient intelligence, psychological warfare, and siege tactics

These strategies culminated in successive victories of the Mahdist Revolution.

Chapter Three: Imam al-Mahdi’s Philosophy on Managing Change

Al-Mahdi led a profound transformation targeting religion, society and governance.

Key indicators include:

- His belief in change itself

- Possession of tools of change

- Presenting himself as a supreme Sufi authority and inspired leader

- Recruiting new and young leadership

While the concept of Mahdism remains theologically contentious, its political utility lay in creating a collective psychological bond that enabled unity, obedience, and mobilization against injustice.

Chapter Four: Imam al-Mahdi’s Philosophy of Managing Diversity

Sudanese society prior to the revolution was fragmented by tribal, sectarian, and class divisions.

Al-Mahdi addressed this diversity by:

- Possessing intimate knowledge of society

- Creating a new unifying bond centered on Mahdism

- Establishing new criteria of affiliation and leadership selection sensitive to regional contexts

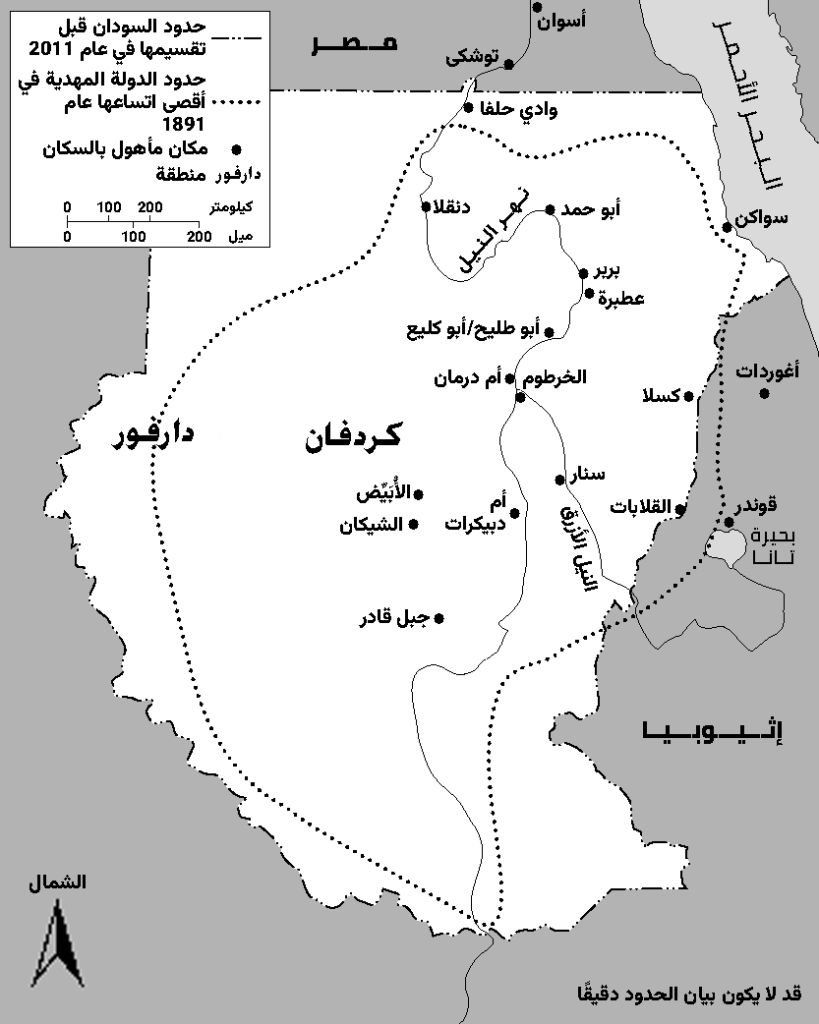

Chapter Five: The Strategic selection of Omdurman

Although al-Mahdi never explicitly stated his reasons for choosing Omdurman as his capital, a careful reading reveals strategic, social and political wisdom behind the decision. Omdurman embodied his philosophy of change and diversity management, producing a unified social and cultural model that later shaped Sudanese national identity.

This social and cultural model initiated during the founding moment continued to evolve organically, giving rise to national movements opposed to colonialism that were grounded in the same philosophy of managing diversity and the same criteria of change adopted by Imam al-Mahdi. A unifying culture subsequently emerged as a shared frame of reference, developing naturally and peacefully in accordance with humanity’s inherent inclination toward coexistence. This, in turn, produced a central cultural identity that often served as a strong bulwark against regression into tribalism and sectarian religious affiliations.

Is there, then, a possibility of a new Omdurman? one capable of shielding us from the perils of regression and the depths of ethnic and religious strife looming on the horizon?!!

Conclusion

We cannot change historical events.

But we have the full right to re-read them through new methodologies, not to reproduce the past, but to understand our present and to look forward to shaping our future.

Leave a comment